Punks And Hippies

There’s a period of my life, almost five years, when there’s no proof I existed. From 1966 I’ve got a couple pay stubs and a single picture of me in the final stages of my sullen greaser phase. Then nothing until 1971, when my brother’s girlfriend photographed me in an Ann Arbor basement, still sullen, but now a budding glam rocker.

Missing altogether is any record of my hippie years. I used to have a couple of photos, one taken in New York in 1968 when I was trying to impersonate Blonde On Blonde-era Bob Dylan, the other a year later, with me looking skinny, scraggly, and rough in some Midwestern crash pad. But they’ve vanished, along with every record, item of clothing, guitar, or keepsake from that era. Nothing remains but memories, and I’m not too sure about those.

A couple of images linger, though. I don’t know if they originated as photographs or as fleeting glimpses in a shape-shifting mirror. In one I’m wearing a slightly too small army jacket, looking sideways with startled eyes, and sporting a short, hand-tooled haircut that looks more like 1977 Johnny Rotten than the languid, flowing locks of 1967’s hippie icons. In the other I’m still wearing the army jacket, and my expression has shifted to dazed and confused. My hair is longer, horrendously hacked up, a mixture of dark brown and garish orange, the result of a badly botched bleach job.

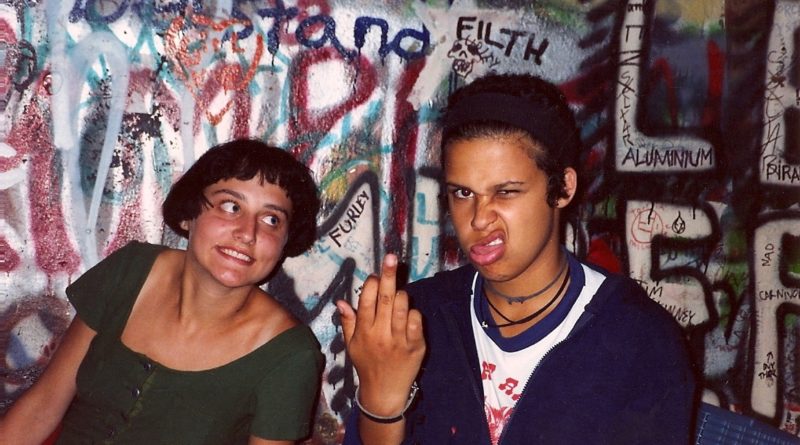

Fast forward to Gilman Street, 1987. The young punks, some as much as 20 or 25 years younger than me, are razzing me, as punks are meant to do, about my hippie past.

“You don’t understand,” I tell them. “Being a hippie back then wasn’t like you see in the movies. A lot of us could have passed for punks. We lived in the same kind of cheap houses, scammed and stole to survive, even our haircuts weren’t that different…”

They didn’t believe me, probably wouldn’t have even if I had the pictures to show them. One of the foundation stones of punk is that you have to hate hippies.

That made a certain amount of sense in 1977. One of the most enjoyable aspects of the early punk scene was pissing off the hippies. Those of us who had actually been hippies, who had only recently cut off our hair and started going to shows at the Mabuhay, tended to be the most militant about it.

I would carry a giant boom box around San Francisco so I could blast the Ramones at anyone that looked vaguely hippie-esque or New Age, just for the joy of seeing the sour looks on their faces. Seems kind of quaint today, with the Ramones having become about as rough and transgressive as the Beach Boys. But in the late 70s, they could reduce a hippie to tears. “Why do you play such hateful-sounding music?” they’d whine pleadingly.

I had a friend named Don, who I met in 1974. His hair was longer than mine, he was wearing a flowered shirt, and invited me to drop acid and listen to the new Jefferson Starship album.

A few years later he’d transformed himself into snarling Don Vinil, lead singer of the Offs, and way punker than me. I ran into him at the Clash show at the Temple Beautiful. “This is pretty great, isn’t it?” he said, gesturing at one of the biggest crowds of punks we’d ever seen.

I’d been standing there having a minor stress attack, worried that the SF punk scene was looking a little too Weimar. I’d just watched a swastika-sporting Sid-punk stroll nonchalantly past a stained glass Star of David (the Temple had started life as a Jewish synagogue). I told Don about it, adding that I wasn’t sure if things were headed in a good direction.

Don gave a nervous laugh. “What, are you turning into some kind of hippie?” I reminded him of that afternoon with the Jefferson Starship, and he gave me a dirty look as he walked away.

A few years after that I gave up on city life and moved to the mountains of northern Mendocino County. Most of the people living in those remote backwoods were old school hippies, the kind city folks thought didn’t exist anymore. I was a minority of one. My tales of Woodstock and love-ins and run-ins with the cops counted for nothing. I had short hair and I listened to that awful music.

It would be a while before they accepted me, and I didn’t make things any easier with my snide remarks about reggae and the Grateful Dead. But eventually I began to feel like a full-fledged member of the community, ironically at the same time that I got re-involved with the punk scene down in the Bay Area. For several years I shuttled between two worlds, feeling as if it was my mission to build a bridge of understanding between country and city, between punks and hippies.

My music and my writing drew on and tried to merge influences from both places. By 1990, when some punks came north to join the Redwood Summer protests, I felt like I was making progress. Folk-punk and crusty-hippie bands began to emerge, for which I accept no responsibility. But that’s about as far as it went. Nowadays both countercultures are becoming more relevant to historians and anthropologists than to current affairs.

But why, I wondered, did they have such disparate impacts on the larger society? I recalled a time in Ann Arbor, at the beginning of the 1970s, when there were so many hippies, and they played such a large role in business, culture, and politics, that in certain sections of the city, you’d think they were running the place.

I’ve never seen a place where punks wielded that kind of influence. You can hear the Ramones played before baseball games and pop-punk backing tracks on commercials, but I think it’s safe to say that punk never integrated with mainstream culture to anywhere near the extent the Woodstock generation did. Some would say that’s a good thing, and I might be inclined to agree, if only because it enabled punk to continue to develop, bubbling unseen beneath the surface, for a couple extra decades.

Despite the popular image of punks as irrational nihilists whose art consists mainly inverting conventional norms and throwing the remains back in society’s face, an astonishing number of professors, scientists, lawyers, doctors, and garden variety good citizens emerged from the punk scene. That was true of hippies, too, of course, and just to keep it fair and balanced, both groups also contributed their share of drug addicts and lunatics.

But I still think the hippies have left a much more noticeable mark, for better and worse. They were far more numerous, of course; they came out of the baby boom generation, the biggest (and, some insist, most annoying) generation in history, whereas the punks grew out of the baby bust that may have resulted at least partially from the hippies’ inability to get or stay married.

You were never going to find half a million punks to sit in a field for a three-day festival, but though there never was and never will be anything like a punk Woodstock, there were fewer normie kids, too, so you’d think the punks could still stand out. But maybe not as long as half of them refused to come outside in the daytime.

Another big difference is that the hippies actively recruited, whereas the punks repelled. In addition to hating hippies, one of punk’s salient characteristics – especially in the early days – was to be deliberately unattractive. If you tried to join up with the hippies in 1967, they’d hand you a flower and tell you they loved you (whether or not it was true). Try the same thing with the punks in 1977 and they’d give you a dirty look and call you a poser.

The punks’ biggest problem – though many wouldn’t consider it a problem at all – was that they were a reactionary movement. They were reacting against the cloying excesses of the hippies, against the self-serving crassness of the politicians, against the deep, abiding stupidity that both British and American society seemed to be wallowing in.

All understandable, of course, but no matter how righteous your cause, it’s never going to be as appealing if you identify yourself mainly by what you’re against. Hippies were selling a wildly idealistic – and yes, unrealistic – vision, but who could be against peace, love, understanding, and the dawning of the Age of Aquarius?

I’ll tell you who: Jello Biafra. The Dead Kennedys’ singer ranted against the “Zen fascists” and the “suede denim secret police.” To hear him, you’d think Governor Jerry Brown’s grooviness overload was the biggest threat to America. Meanwhile, Ronald Reagan, an actual bad guy, if not an outright fascist, was marching into the White House. That’s not to say Brown should have been above criticism, but punk’s insistence on rebellion über alles too often contributes to one of punk’s other big failings: missing the point.

The hippies – if you include their cousins, the New Left – could put hundreds of thousands of people in the streets to oppose the Vietnam War. When the punks show up for a protest, they might come in the hundreds for a big one, in the tens or dozens otherwise. On the other hand, while many old hippies have turned into Trumpists – or apathetic nonparticipants, which is almost as bad. the punks have, for the most part, kept the faith.

Of course almost from the beginning there was a small but virulent right-wing element on the punk scene, usually but not exclusively among the skinheads. And of late, I’ve noticed a sprinkling of elderly and middle-aged punks who are quietly or even loudly pro-Trump. Not always because they agree with his policies; sometimes they just do it to piss people off. At heart they’ve never gone beyond the swastika-in-a-synagogue phase.

It’s hard for me to identify with either the hippies or the punks anymore (I’ve still got a soft spot for my greaser years, even though it’s amazing that I survived them). Many of the people I care most about have roots in one or both of those scenes, but my favorites are the people who’ve risen above them while still drawing sustenance from what they learned there, treating their memories and experiences as compost for the soul.

I’m probably getting too old to hook up with another counterculture, if such a thing even exists anymore. I wouldn’t be surprised if it doesn’t, maybe because mainstream culture is already contrary enough. I will say that for all their negativity and reactionary tendencies, the punks were more likely to pool their efforts and create lasting institutions. The hippies were content to sign with a major label; the punks said, “The hell with that, I’ll start my own.”

I don’t think it’s a coincidence that Bay Area punks (and Northern California hippies) were more productive than their counterparts elsewhere. The local tradition of activism and creating alternative institutions offered the punks something more appealing than getting fried on drugs and beating the hell out of each other, which tended to be the undoing of the Los Angeles and New York scenes.

We talked about that in Turn It Around: The Story Of East Bay Punk, and a number of other books, studies, and articles, and it rings true. But who gave the Bay Area that tradition of activism and alternatives? Yep, the hippies and student radicals of the 60s. Not to mention the beats, the civil rights protesters, the union organizers, all of whom laid down the soil in which the hippies could flourish, but most of the punks are too young to remember them.

So love it or not, though it may stick in your, craw, you’re joined at the hip, punks and hippies, two sides of the same coin. And just prove it, you’ll both hate me for saying so.

Larry, as a then 18 year-old who razed you about your age (which was younger than I am now) at Gilman back in ’87, I probably should apologize, but my god all the years of “You missed out man” and “You’ll never have what we did” messages of those who were teens and young adults in the ’60’s was grating, that my and the majority of my classmates parents divorced and have us shuttle between houses with a parade of the new “love the one your with” boyfriends and girlfriends of the week, would get high in front of us, and basically just leave us to raise ourselves didn’t give a good impression, plus just seeing the general decay around (the explosion of homelessness in the ’80’s) didn’t engender respect for my elders and how they made the world.

Question authority?

What authority?

A couple of the teachers would try to get pot from and grope my 12 and 13 year-old classmates, and tried to blur the lines between kids and adults.

Becoming a punk was EASY!

Trying to figure out how to be a “square” was much, much harder, I remember telling you (I think around ’90) “I actually want the white picket fence, I just don’t know how to get it”. I finally did, but it took 30 years. It shouldn’t have been so hard, still bitter about it, and the young adults of today have even longer odds of getting there (at least now there isn’t the sound of gunfire every month like in the mid ’80’s).

Very interesting article and reflection on those times. Born in 93, heavy influenced by Green Day and their history, I never quite understood the negative buzz between the punk and hippie scene I recognized while satisfying my zeitgeist study of my favourite band via the depth of early youtube from then 10-15 year old videos of appearances in the 90’s.

I was always and am still feeling sympathy for both cultures, for me (maybe because of a slightly romatizing retrospective) those movements weren’t excluding each other.

The excellent read above made me get a feel for why it has been that way, while James comment made perfect sense to me and left me thinking about society again..

Cheers from the old world and stay safe