On The Plains Of Abraham

At school we were taught that the crucial battle, the one that determined Canada would be British rather than French, took place on the Plains of Abraham, just outside the walled city of Quebec. As was the case with many things I learned at school, this was partly but not completely true.

Perhaps for simplicity’s sake – we were young children, and our teachers, nearly all nuns, were not highly educated themselves – we were led to believe that the British forces gave the French a good kicking, raised the Union Jack over the promontory on which Quebec is situated, and Nouvelle-France, France’s vast North American colony, was done, kaput, finie.

Never let the facts get in the way of a good story, of course, but it’s only fair to note that the Union Jack didn’t officially exist until 1801 – 42 years later – and the war itself would carry on for another four years before France officially surrendered. My mom’s relatives and ancestors were English Canadian – the last Frenchman in the lot had learned English and lit out for Ontario a couple of centuries previous – so it was understandable that they saw the British victory as a Good Thing. I have no idea why my teachers, most of them Polish refugees from the Second World War, thought likewise, but they did.

When I visited Quebec City for the first time, somewhere in the late 1970s, I naturally visited this historic site, but like most battlefields not currently in use, it failed to impress. Without a battle, a battlefield is just, well, a field. In the absence of any distinguishing features like trees or rocks or cliffs, it doesn’t differ greatly from a hugely expanded version of your front lawn.

About the only thing that set the Plains of Abraham apart from a standard-issue flat field was that it wasn’t entirely flat. At the far end, it took a sharp upward turn toward the base of the old city walls. That elevated portion would come in handy on the July Sunday in 2023 when I revisited the scene. It helped create the effect of an open-air amphitheatre, giving spectators an opportunity to lounge on the grass while watching the performance. Or would have if the grass hadn’t been soaking wet from an all-day rain…

But wait, a performance? What performance? Was the Battle of the Plains of Abraham, aka the Battle of Quebec, about to be re-enacted for the benefit of the millions of tourists who flock to North America’s oldest (St. Augustine, Florida claims otherwise, but let them fight it out) and only walled city.

No, not exactly. But high fences, nearly as forbidding as the border wall that separates Israel from Palestine, had been erected around the entire field, ticket takers and security guards installed in place, and the gates were about to open for the Festival d’été de Québec, the Quebec Summer Festival. It’s been going on since the 1960s, even though I’d managed never to hear of it until now, but apparently it’s a pretty big deal. What’s more, tonight was the closing night, and my friends, Green Day, were headlining it.

This would be the first gig, concert, performance, whatever you want to call it, that I’d attended in at least four years. Honestly, I can’t remember when the last one was, but I assume it was sometime in 2019. I spent the latter part of that year in China (no, I didn’t bring COVID with me, though I admit the timing is suspicious). I travelled nearly all of 2019, so it may well be that I didn’t see any shows that year. My last vivid, undeniable memory of a live musical experience was the Gilman Street Lookouting in January of 2017, at which I was both spectator and performer. Of course, there was Grant Lawrence’s mid-pandemic Lookout Zoomout (beginning to see a theme here?) in 2021, but that was totally virtual.

Let’s just say it had been a long time, probably the longest time since I started going to see bands in my early to mid-teens. It might sound strange, but I was a little nervous. All through the plague years I’d avoided, for obvious reasons, the cramped basements and indoor venues where I typically saw shows; this one would be entirely outdoors and set on the biggest field I’d seen since the original Woodstock in 1969, so I wasn’t that afraid of getting sick. Maybe I was just nervous about being around that many people.

There was some doubt as to whether the show would even happen. It had been raining, often heavily, all day, and the forecast said the wet weather would continue into the night. Even if the bands went ahead and played (the stage, at least, was sheltered from the rain), it would be dispiriting to do so in front of a muddy, half-empty field). Oh well, I thought; I was here mainly to meet up with old friends. I almost didn’t care whether the show happened or not, but an awful lot of other people would be bitterly disappointed if it didn’t.

Anyway, too late to turn back now; we were already in Quebec City, and by we, I mean myself and Jim Allison. Back in the East Bay of the late 80s/early 90s, Jim played guitar in a band called Fuel (not the fake, “alternative” Fuel that came along later, stole/borrowed the name, and then had the gall to threaten the OG Fuel with a lawsuit for stealing “their” name) (the OG Fuel won that dispute, thanks in part to evidence that they’d been around much longer; their 1990 EP on Lookout Records helped prove that point).

Fuel were somewhat of an anomaly in the Gilman/East Bay scene, in that their sound owed more to the East Coast Dischord sound (“Fuelgazi,” the usual East Bay smartasses sometimes called them), but what modern-day cataloguers and categorizers often don’t get is that there was never a single Gilman/East Bay “sound.” What made that era special was the way bands and performers of all types temporarily put aside their differences and worked and played together.

Jim lives in Montreal now, as do I, so when he suggested driving to Quebec (about three hours up the road/down the river, depending how you look at it), I said, sure, why not? Fuel were part of a nexus of East Bay bands that also included Monsula and the Skin Flutes (later, after the boys graduated high school, known as Sawhorse), both of which benefited from the presence of Bill Schneider, who would later go on to play a crucial role in (I’m probably forgetting one or two) Uranium 9-Volt, Pinhead Gunpowder, the Influents, and the Coverups. Bill also is the guy who, as much as anyone, is responsible for getting the not-insubstantial Green Day touring machine on the road and keeping it moving in a more or less straight line.

Every time I marvel aloud at Bill’s ability to oversee a multiple-ring circus while remaining as cool as the proverbial cucumber and even allowing himself the occasional smile or guffaw, he gives me an aw-shucks rebuttal, to the effect that he doesn’t do much at all, even once claiming “Basically, I’m just along for the ride.” False modesty notwithstanding, the guy impresses me immensely, and honestly, I’m not sure what Green Day would do without him. Bill and Jim have stayed in touch ever since the early Gilman days, and as for me, in addition to wanting to see the whole crew, I had a special mission in mind.

My first book, Spy Rock Memories, is due for a 10th anniversary reprinting/second edition, and, as with album reissues, we needed some bonus tracks. I hit upon the idea of interviewing Tre Cool, who grew up on Spy Rock and played in a band with me for five and a half years before joining Green Day. My book was about living on Spy Rock, how it changed me, altered my course in life, and essentially laid the groundwork for Lookout Records and all that flowed out of it.

It occurred to me that Tre, having seen Spy Rock through the eyes of a child, might have a wholly different perspective, and this proved to be the case, but more about that later. First I had to find him, which is not always easy. But after navigating our way through the tourist-clogged streets, Jim and I eventually tracked down Green Day in a restaurant near the heart of the old city.

They were just finishing dinner and spirits were high, except for Billie Joe, who seemed slightly subdued, and headed back to hotel after a brief exchange of greetings. Almost everyone else – Green Day travel with a quite a large crew – adjourned to a nearby pub, where I found myself seated between Mike, who regaled me with his latest ideas on politics, and Tre, who chattered away with the same manic exuberance I’ve been used to ever since he was a hyperactive nine-year-old.

The staff of the pub were surprisingly cool, not making a big deal out of having celebrities in their midst, but that didn’t stop them turning us out into the streets when closing time came around, and we stood in front of the hotel for another hour being the kind of people who usually annoy me by talking loudly outside my window when I’m trying to get to sleep. I told the sad story of the Buzzcocks’ Pete Shelley, who blamed Green Day for somehow stealing the success he thought should have been rightfully his (I got an especially vituperative earful from him for having helped Green Day along the way). Tre told me that I smelled a lot better these days than I had back when we were playing together in the Lookouts.

We made plans for the next day; Bill said the easiest thing would be for us to ride into the festival grounds with the band and crew, and Mike texted me a copy of the schedule. It said that we’d be getting a police escort, and I mentioned that while I’d had police escorts before, most of them had involved handcuffs and jail cells. As it happened, though, the police never showed up, which disappointed me a little, but at the same time left my PTSD untriggered (just kidding, I don’t really have PTSD) (at least that I know of).

I’ve been backstage at big festivals before, but this was kind of next level. In addition to the usual tour laminate, we were also issued wrist bands that contained a microchip (I’m sure it’s only a matter of time before musicians and crew get the microchip temporarily or maybe even permanently implanted). You had to have it scanned to go anywhere, and they could even use it to determine whether you’d had more food than you were entitled to in the catering tent.

Jim and I walked out onto the stage a couple hours before showtime to survey the still mostly empty field. The rain, semi-miraculously, was stopping, though you still had to watch your step if you didn’t want to step on a slippery spot and fall on your ass. Tre did a run-through on his drums, which were set up inside a little tent at the back of the stage, decided the snare didn’t sound right, and twisted and turned some keys until it did. Then we adjourned to his dressing room for our interview. Even though the temperature outdoors was quite cool for midsummer, there was an air conditioner running full blast. “You should turn it down,” I said, and Tre did so. “No, turn it down some more, it’s still really cold in here.”

Tre looked at me. “Larry, this is my room, not yours.” He wasn’t mean about it, just matter-of-fact, but it reminded me of how things had changed. Back in the Lookouts days, especially when Tre was still learning to play the drums as a rambunctious 12-year-old, I’d gotten in the habit of ordering him around. Whether that was right or wrong, 38 years had passed, and the balance of power had distinctly shifted.

The interview turned out far better than I’d hoped. Originally my idea had been just to collect a few ideas and turn it into an article – essentially acting as a ghostwriter for Tre – but he had so many awesome things to say, and said them so articulately, that I decided to print it as a straight interview. The best thing about it, apart from revisiting old memories and hearing some stories I’d never heard before, was learning about how different Tre’s Spy Rock experience had been from my own. He was nowhere near as nostalgic about it as I can be, but there was at least one thing we agreed on: it was impossible to spend years living on that mountain without being irrevocably marked and changed by it.

Interview done, I walked outside and immediately ran into Billie Joe, who seemed a lot more ebullient and upbeat than he had the previous night. We talked about a host of things, but the one thing I especially wanted to tell him was that I’d just listened to a recording of him singing at the show a couple nights previous.

“Your voice sounded richer and warmer than it ever has before,” I said. “It reminded me of Sinatra when he was coming into his prime.” It might sound like a strange thing to say to a world-renowned punk rock singer, especially one who’s been singing very successfully for most of his life, but I also knew that Billie had sung Sinatra songs with his dad long before he ever set foot in a punk rock venue, and was pretty sure he’d get what I meant.

Billie’s been listening to my ideas, some of them pretty good, some of them pretty cracked, ever since the 1980s, and I’m never totally sure whether he appreciates them or just puts up with them for the sake of a longstanding friendship (probably a bit of both), but I felt it was important to let him know how impressed I was. When you’ve heard someone singing for the past 35 years and can still notice a significant improvement, I think it’s worth mentioning.

I heard a band start to play, and it sounded familiar, so I went out to the stage to check it out. It was Bad Religion, the first time I’d seen them since the early 1990s. I’d always liked them, but I’ll admit to having not kept up with them in recent years. “Their songs all songs all sound the same,” someone once told me, “but it’s a really good same.”

I’d have to agree. I didn’t recognize most of the songs at first, but they maintained the flow and harmonies of what I (and quite a few others, I think) consider their “classic” trio of albums, Suffer, No Control, and Against The Grain. I got impatient when they seemed to take forever before playing my all-time favourite song, “I Wanna Conquer The World,” but when they finally did, it was well worth the wait. It was the first time in years that I jumped around and sang along with a band. Also well worth the wait.

I didn’t recognize several of the members, though one of them, Brian Baker, had come up to me earlier and said, “We’ve met before, haven’t we?” I said I wasn’t sure, but I didn’t think so, and he said, “Well, I know you, and I’m a great admirer of your work,” which I took as high praise, considering he’s a considerably more legendary character than I could ever hope to be.

One Bad Religion member who was missing, and who I’d been looking forward to seeing, was Brett Gurewitz. “Oh, he only comes out on tour once in a while these days,” someone told me. I have to admit I found that odd. Even though he’d once told me that he considered running a music business to be as much of an art as the music itself (an idea which I didn’t fully agree with at the time, but appreciate a lot more nowadays), I found it hard to believe he could pass up an opportunity to play for somewhere between 80,000 and 100,000 people (someone associated with the festival told us 95,000 tickets had been sold in advance; whether everyone who bought them showed up was hard to tell, but by the time Green Day took the stage, there were more people in one place than I could remember seeing at any time since, once again, Woodstock.

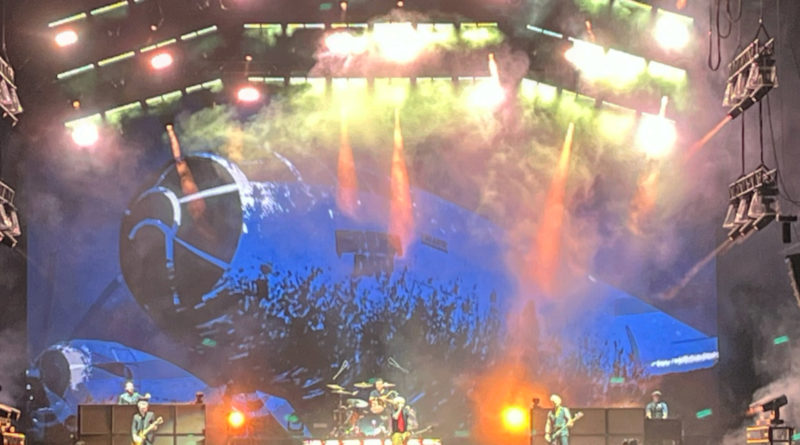

Bill Schneider told us that while we were free to watch the show from the stage as we had with Bad Religion, he’d recommend against it. “You won’t hear anything except the drums,” he said, “they use in-ear monitors for everything else.” With that in mind, he led us out in front of the stage and down a long wooden walkway bordered on both sides by legions of fans until we’d reached the sound and light booth. For listening it was perfect; we were standing next to the people who controlled everything that happened on the stage except for the actual performance. For watching, it wasn’t quite as great; we were far enough away that the band were dwarfed by the giant video displays behind and to either side of them.

If you’ve attended a Green Day show anytime in the last ten years you’ll have a general idea of what they played, though Billie called an audible just before they went out on stage, announcing that they were going to play a new song called “1981.” “Wait a minute,” someone said (if I could remember who, I’d tell you), “How does that one go again?” At their previous show in Milwaukee, multi-instrumentalist Jason Freese had delivered a note-perfect rendition of the 1950s classic “Tequila”; he and the band had figured out how to play it only seconds before stepping out on the stage.

But even though I’d heard all the songs except “1981” before, the show flowed together really well. Billie did his usual “ay-oh” call and response thing, but a little less so than I was used to. I once asked him why he did that instead of just playing the songs straight-up the way the band did in the early days. Billie reminded me that when the band was just starting out, their shows could be chaotic and unpredictable, and not always in a good way, with long bits of banter and the occasional broken string stretching out the intervals between songs; somehow, I had forgotten that part.

As for the “ay-oh” routine, he told me, it was necessary when playing for large crowds, especially when lots of young kids were present (tonight’s show ranged from small children to venerable greybeards and everything in between), because otherwise the crowd could get over-agitated and maybe do damage to themselves. It gave me a new image, of Billie wielding his hands and his magic to guide the crowd like a symphony conductor would an orchestra.

There were many high points in the set – unlike the punker-than-thou crowd, I genuinely love some of the big hits, like “Holiday,” “Wake Me Up When September Comes,” and “Boulevard Of Broken Dreams.” But the one that hit hardest was a song I hadn’t paid much attention to when it first came out, gradually grew on me, and then, unexpectedly, when I was at an emotional low point over something or other, simply grabbed hold and wouldn’t let go.

When it’s time to live and let dieAnd you can’t get another trySomething inside this heart has diedYou’re in ruins

It’s called “21 Guns,” of course, and although to this day I have no idea what it has to do with either guns or 21, I remember beginning to come to terms with my own mortality when I heard that “live and let die” line (I think it was also around the time my mother died in 2015), and feeling utterly alone in the universe, yet somehow, poignantly okay with that.

I wasn’t expecting to feel that way all over again in 2023, but I did. A wave of gratitude and fulfillment washed over me at the thought that I’d played a part, no matter how small, in the evolution of one of the world’s greatest rock and roll bands (the greatest currently active, and by some margin, in my opinion). “We live in history like we live in air,” Todd Gitlin had once told me when I took his class at Berkeley, and while I don’t always appreciate what history does with us or to us, this particular aspect was pretty great.

As usual, Billie closed the show with his solo rendition of “Good Riddance (Time Of Your Life”) (“the Seinfeld song,” for those who don’t follow Green Day or rock and roll). How one kid with an acoustic guitar (okay, he’s 51 years old, but I’ve known him since he was 16, and he’ll always seem at least a little kid-like to me) can command the attention of a massive audience and leave them completely spellbound has always amazed me. One time, many years ago, I stood behind him at Madison Square Garden as he did the same number for a mere 20,000 fans. Even then I marvelled at how it felt like a campfire singalong, with a host of cellphones flickering like fireflies from the rafters.

This crowd might have been as much as five times larger; the only difference was more fireflies and an even more rapt audience. The show was over, and we headed back to the catering tent for a late night make-your-own-poutine supper (vegan and vegetarian options included). I complimented Billie for perfectly nailing the falsetto part in “21 Guns” (it’s not easy; try it if you don’t believe me), and then a minute later, shouted at him to bring me one of the cupcakes that had just been laid out on the table (“No, not that one, a vanilla one!” I added). It was kind of like when I casually told (ordered, almost) Tre to turn down the air conditioner, but if Billie was annoyed at being treated like a hired hand after being the centre of attention for 100,000 fans, he made no mention of it.

Everyone sat around for another 30 or 40 minutes, sharing stories and reminiscences. It occurred to me that I was sitting at a table with three quarters of Pinhead Gunpowder and wouldn’t it be great if sometime they opened for Green Day, but kept the thought to myself. I suggested to Jason Freese that he consider playing “Harlem Nocturne,” to my mind the greatest saxophone solo ever, but unlike “Tequila,” he was already familiar with it.

Then it was into the vans and back to town. The goodbyes went on into the night, and a few people set up the rudiments of a party in the hotel lobby, but for most of us, it was bedtime. The next day Green Day would be headed back to California and Jim and I would take a leisurely route back to Montreal, driving through the countryside along the south bank of the St. Lawrence River. In 1945, shortly after my dad got back from World War II, he and my mom took his ’39 Buick and, for their honeymoon, followed that same river all the way to where it meets the Atlantic at Gaspé. It would provide a nice little coda to be able to say that I was named for the river (or the river for me), but sadly, neither is the case.

Nevertheless, rural Quebec is stunningly beautiful, and as Jim drove, I half took in the sights, and half mused over the different directions my life has taken. Whenever I briefly re-enter the big-time music scene, it’s hard not to wonder what might have happened if I hadn’t abruptly walked away from it, and it’s tempting to regret the things I might have seen and places I would have gone if I hadn’t.

But as much as I admire and appreciate Green Day, and stand in awe of the way they’ve managed to not just survive, but thrive, in a world where pitfalls are plentiful and few musicians or groups last even a fraction as long as they have, ultimately I accept that they went their way and I went mine, and both of us have wound up where we were meant to be.

My life is far quieter now, and it’s highly unlikely that I’ll ever walk out on stage in front of 100,000 people unless I’m standing behind the band that they’re actually there to see, but whether I’m walking down a late-night Montreal street where the loudest sound is the wind in the trees, or in midst of a wildly cheering crowd sharing their enthusiasm for my favourite band, it’s pretty great to be alive, and I thank Green Day for once again reminding me of that.

Thank you for this piece, Larry. Accidentally stumbled upon it on Facebook out of all places and it was a great read.

I was at the show that night – what a great time we had! I think Billie’s rendition of 21 Guns was pretty exceptional that night – I’ve never paid much attention to it, but for some reason, it really hit me during the concert, and I somehow felt the song in a way I’d never had before.

It’s indeed pretty great to be alive and Green Day never fails to remind me of that during their shows.